In May 2025, the KBR museum has reopened its doors with an extra narrative, with an emphasis on music from the 15th and 16th centuries. And that is no coincidence: during this period, our region played a starring role in the rise of polyphony – a musical revolution that changed Europe for good.

From one voice to an interplay of sounds

Polyphony is music with several independent melodies played simultaneously. While this might sound trivial today, in medieval times it was a pioneering step. Until the 10th century, music was mainly monophonic. A song could be sung by several singers at the same time, yet comprised a single line of melody, the most famous example being Gregorian church hymns. Monophonic music was generally transmitted aurally and sung from memory. The text was generally the only record. That changed as from the 10th century. An increasingly refined system of notation for pitch and rhythm emerged, allowing composers to record music much more precisely. That made way for more complex multi-voice music: the birth of polyphony.

Curious to hear the sounds of early polyphony? Listen to an impressive 12th-century version of Viderunt omnes.

Polyphony began as a form of decorated plainchant for use in the church. As musicians became more accomplished in writing and composing music, the applications of polyphony became ever wider. Around 1470, the music theorist Johannes Tinctoris made a distinction in polyphony between three genres: the most important of these was polyphonic compositions for mass, then came motets to Latin texts, and the third and smallest category gathered songs in the common language.

The development of polyphony unfolded throughout Europe and over several centuries. Yet, some places — courts, churches, cities or even whole regions or states — played a more important role than others. This was linked to the volatility of musical patronage and the presence of influential composers.

Until the 14th century, the fundamental innovations took place in music notation and composition, particularly in modern-day France and Italy, however, in the 15th century, the centre of musical activity shifted north. Early that century, English composers began experimenting with richer harmonies. By the middle of the century, this innovative ‘English style’ gave a creative boost to music in the Low Countries.

Sounds for the Dukee pour le duc

After conquering the Low Countries, Duke Philip the Good no longer maintained his court’s emphasis on the south, but on cities such as Brussels, Lille and Ghent. Despite being small, the court was wealthy and impressive. It soon set a standard for other European rules, with its prosperity and refinement. Music played an important part in this. In 1445, the court chapel, or army of musicians performing music at the court, was described as ‘among the biggest and best maintained’ at the time. Under Philip’s son, Charles the Bold, the chapel’s growth continued. Some of the most famous composers from the 15th century worked there, including Gilles Binchois, Antoine Busnoys, Robert Morton and Hayne van Ghizeghem. Their music can be found in manuscripts all over Europe. KBR even possesses a music manuscript that was made at the court chapel of Charles the Bold and which accompanied him and his singers on the battlefield during his military campaigns.

Antoine Busnoys, Anthoni usque limina. ms.5557, fols. 48v-49r.

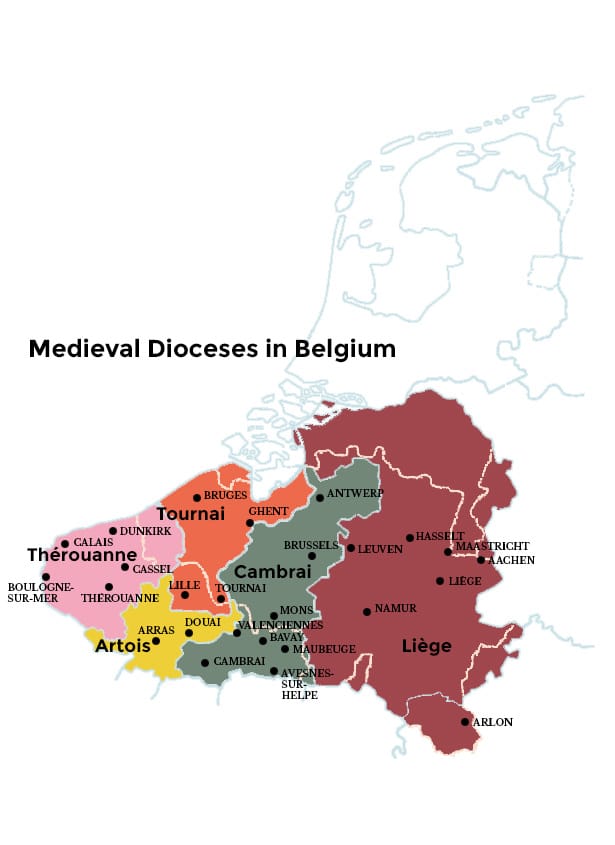

Despite its great investment in music, the Burgundian court employed adult singers alone. What really set the Low Countries apart in Europe were the great choir schools attached to cathedrals – particularly those in Tournai and Cambrai. Until the mid-16th century, these two dioceses governed almost the entire territory of the southern Low Countries. This is also where the most talented choirboys from the region went for their musical training.

source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Belgian_Medieval_Dioceses.png

Cambrai cathedral played a key role in musical history, mainly because Guillaume Du Fay was employed there – he was Europe’s most influential composer in the second half of the 15th century. Less is known about the choir school in Tournai, although the cathedral is still there today. Even so, it appears that great composers were trained there too, such as Josquin des Prez, Pierre de La Rue, Gaspar van Weerbeke and Marbrianus de Orto. Elsewhere, in cities such as Bruges, Ghent and Antwerp, the local collegiate and parish churches supported young talents like Jacob Obrecht, Alexander Agricola, Heinrich Isaac and Mattheus Pipelare.

Music and manuscripts at the Habsburg-Burgundian court

Following the death of Mary of Burgundy in 1482, the musical activity in court fell silent. However, around 1500 there was a revival in court music, first under her son Philip the Handsome and later under her daughter Margaret of Austria, who led the court as regent. She gathered some of the best composers in their generation. One of the most important was Pierre de La Rue, who entered service in 1492 and spent his whole career serving the court. He wrote thirty masses, including the impressive Missa Sancta cruce.

Would you like to hear the mass by La Rue? Discover it here.

Pierre de La Rue, Missa Septem doloribus. Ms. 215-216, fols. 1v-2r.

The most extraordinary aspect of this court was the production of dozens of luxurious musical manuscripts on parchment. These books, with music from La Rue, other court and fellow composers were presented as gifts to kings, emperors and popes. Some of these magnificent manuscripts remained in the Low Countries and are now in the KBR collection.

Keen to hear the sounds of the late Middle Ages? Come and visit the KBR museum and listen to the impressive polyphony by singers from this period.