If you stand on the Mont des Arts and look closely at the KBR building, you can spot the outer wall of the Nassau Chapel through the monumental peristyle. The chapel is incorporated into the modern building of the national library and is today part of the KBR museum. But how did the chapel come to be there?

A chapel full of splendor

Where the Nassau Chapel now stands, there used to be a much more modest chapel dedicated to St. George and St. Catherine. In 1344 Willem van Duvenvoorde received permission from the diocese of Cambrai to add this chapel to his impressive mansion, on the condition that he celebrated Mass four times a week at the chapel.

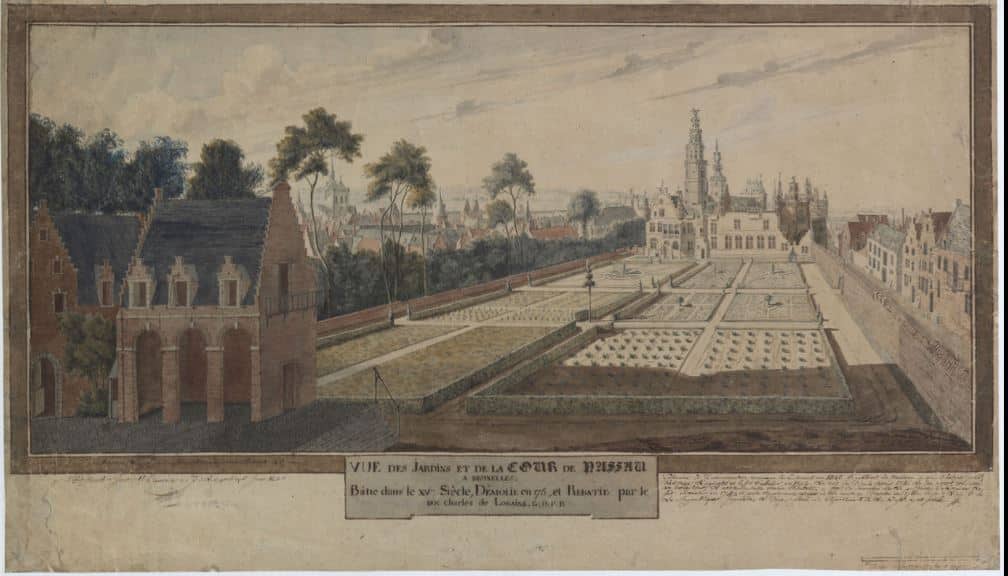

At the end of the 15th century, the Nassau Chapel –or St. George’s Chapel, as it was known at the time– was then built for Engelbert II of Nassau, general stadtholder of the Burgundian Netherlands under Philip I. Around 1520, the structure in Brabantine Gothic style was completed. The chapel was part of the Palace of Nassau, one of the most beautiful residences in Brussels at the time.

An eventful history

In the 16th century, the court experienced numerous vicissitudes. The Spanish government confiscated the Palace of Nassau, but returned it a century later –after the fire at the Coudenberg Palace– to the descendants of the Orange-Nassau family. In 1731 the Palace of Nassau became the seat of the Court of the Netherlands. All that time the Nassau Chapel remained open to the public: worship services were held in the chapel throughout the Ancien Régime.

In 1756, Governor Charles of Lorraine bought the palace from its last owner and had it rebuilt in the neoclassical style. Only the chapel remained untouched.

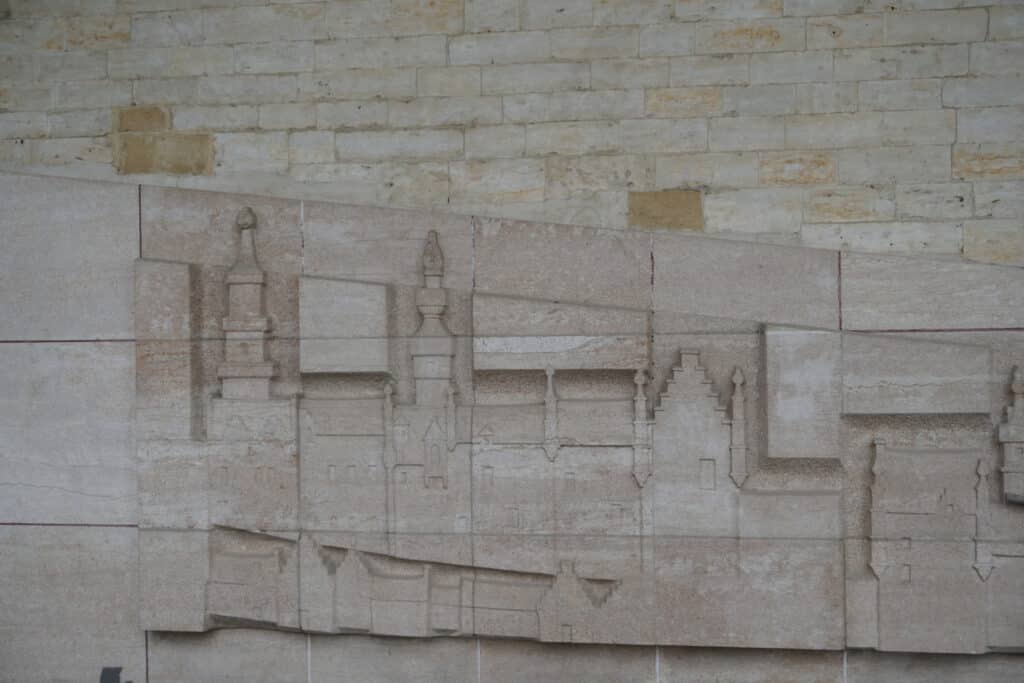

Bas-relief

This bas-relief (visible at the bottom left of the outer wall of the chapel) shows the silhouette of the (now disappeared) Palace of Nassau. Sculptor Georges Dobbels made it in 1969.

The access ramp located right next to the chapel is reminiscent of the slope of the former Rue Montagne de la Cour, which was located on the same place.

A place full of history

From the 19th century onwards, the chapel had very different functions. It was rented to a brewer until 1839, then used as a temporary storage place for the oeuvre of sculptor Mathias Kessel, which the state purchased in 1839 and which today forms the core of the collection of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium.

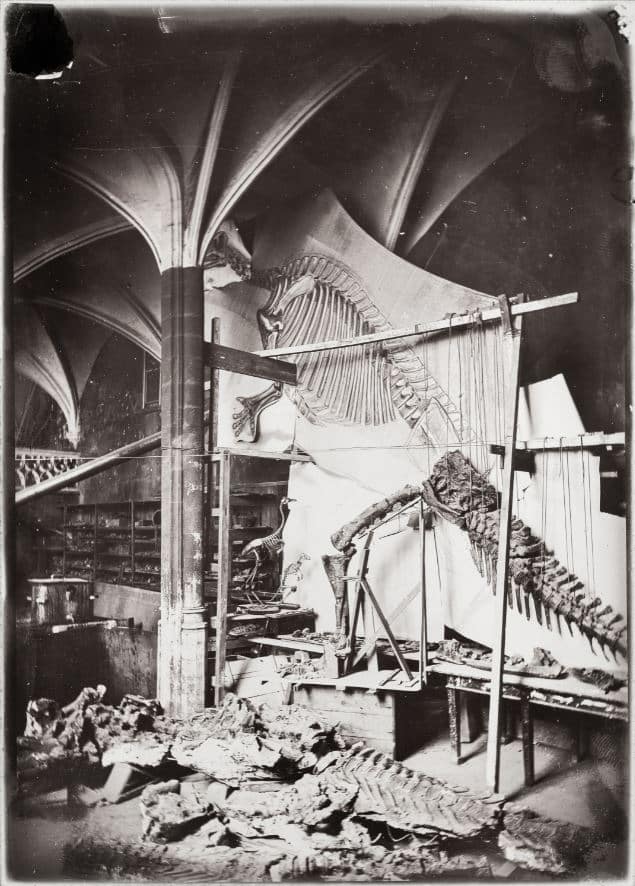

In 1862, the chapel served as the laboratory of the Royal Museum of Natural Sciences, which opened in 1814 in the former Court. Thanks to old photographs, we know that the assembly of the iguanodons from Bernissart, discovered in 1877, took place in the Nassau Chapel. The location of the beam used for this delicate undertaking is still visible in the chapel today (see photo below).

In 1891, the collections of the Museum of Natural Sciences moved from the Palace of Charles of Lorraine to Leopold Park. In 1895, the Nassau Chapel was used as the catalog room of the International Institute of Bibliography, which remained there until 1920.

In 1923, the chapel was converted into a reading room for the State Archives, which replaced the Museum of Natural Sciences in 1891. It continued to serve this function until 1958, when the Royal Library was built.

Typical Gothic architecture

Structure and architecture

The elegant Nassau Chapel was built in Brabantine Gothic style. With its flamboyant decoration (the stained glass windows and the gallery balustrade), it is reminiscent of the style of the Keldermans family, famous architects from Mechelen.

The structure of the original building consists of successive vaults supported by slender round columns without capitals. The ribs come directly from the shafts.

The building is lit by four windows with pointed arches and balustrades.

In the Gothic alcove on the outside of the chapel you can see the statue of St. George. Or rather a copy, because the original has not stood the test of time.

Above the former entrance door is a stained glass window with the coat of arms of the Orange-Nassau family, by artist Sem Hartz (1969).

The interior of the chapel

Across from the spot where the altar used to stand –it was probably removed during the French rule– a gallery was built, supported by two low arches. This gem of late Gothic architecture remains intact today.

The chapel must have been decorated with murals, some of which could still be seen behind the old altar in the middle of the last century.

Gravestones

A gravestone was bricked into the wall under the gallery in September 1930. The faded inscription reads “John Hans/ Minor Canonicus“. This Canon from Cambrai died in 1461, but there is no evidence that he was actually buried in the Nassau Chapel. There used to be, however, the tomb of Philippe Dale, who died in 1521. This illustrious figure was the squire of Emperor Maximilian and the maître d’hôtel of Philip I and Charles V.

Philippe Dale’s tomb, a magnificent tombstone carved in stone, was removed in the late 19th century and transferred to the Museums of Art and History. It is very likely that another stele, that of John Hans, was put in its place.

Another gravestone from 1520 was also moved. The epitaph refers to a certain “Jonkheer Wijnant van Hasselholt” and is also kept in the Museums of Art and History.

An inventory with a story

In the diary of Dürer

Like the exterior of the palace, its furnishings were also very opulent. During his trip to the Netherlands in 1520 and 1521, artist Albrecht Dürer was invited to the court of Nassau. He describes the palace as “magnificently built and beautifully decorated.”

In his travel diary he also writes: “In the chapel I saw the painting of Master Hugo (…)”. Dürer is undoubtedly referring to a painting by Hugo van der Goes, although no trace remains of it today. Van der Goes famous was an important Flemish painter in the 15th century.

Garden of Delights

Although Dürer does not write about it, it seems that the Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch (which now hangs in Madrid in the Prado Museum) once adorned the Nassau Palace.

Another little anecdote: Dürer also writes that he saw “two great and beautiful halls and all the treasures in the different parts of the palace. As well as a large bed in which 50 men could lie. This residence is situated high and offers a beautiful view that can only amaze. And I think that in all German areas there is nothing like this.”

Gold brocade altar cloth

Lastly, a precious piece of furniture that is also kept today in the Museums of Art and History: the altar covering made of gold brocade (‘or nué’). This embroidery from Brabant, dating from the first half of the 16th century, was formerly known as the antependium of Grimbergen. The museum also preserves a replica of the interior of the chapel.

In part 2 of this series on the Nassau Chapel, you will read about its miraculous resurrection in the 20th century.