Who is Livy?

Livy (circa 59 BC – 17 AD) was one of the most important Roman historians. Along with Virgil, Horace and Ovid, he brought about a golden age in Latin literature. If you studied Latin, you have almost certainly read a text by him.

Livy was such a masterful story-teller that all his predecessors and successors were consigned to oblivion. We mainly know the story of Rome’s earliest history, of the foundation of the city or of Hannibal’s quest across the Alps as he wrote it.

However, he did not do any original scientific research: writing history in his time was largely a question of talking about what others had already recorded afterwards in as gripping a way as possible. This did not involve any research into documents.

Small legacy, great author

Livy is mainly known for his monumental work “Ab Urbe condita” (From the foundation of the City). It tells the history of the city of Rome, from the founding to the time of Livy himself. A highly ambitious project, as he is describing a period of no less than seven centuries in thousands of pages.

“Ab Urbe condita” was 142 book scrolls long. Far too many to be copied out by hand each time. It was no wonder, then, that some brief overviews of it were soon made. Sadly, the full text was largely lost: barely 35 of the 142 books were preserved.

Livy’s work was grouped into five and ten-book parts: the latter are referred to as “decades”. In Antiquity and the Middle Ages, these decades were probably in circulation as separate wholes, which explains why there is no single manuscript for all the books preserved.

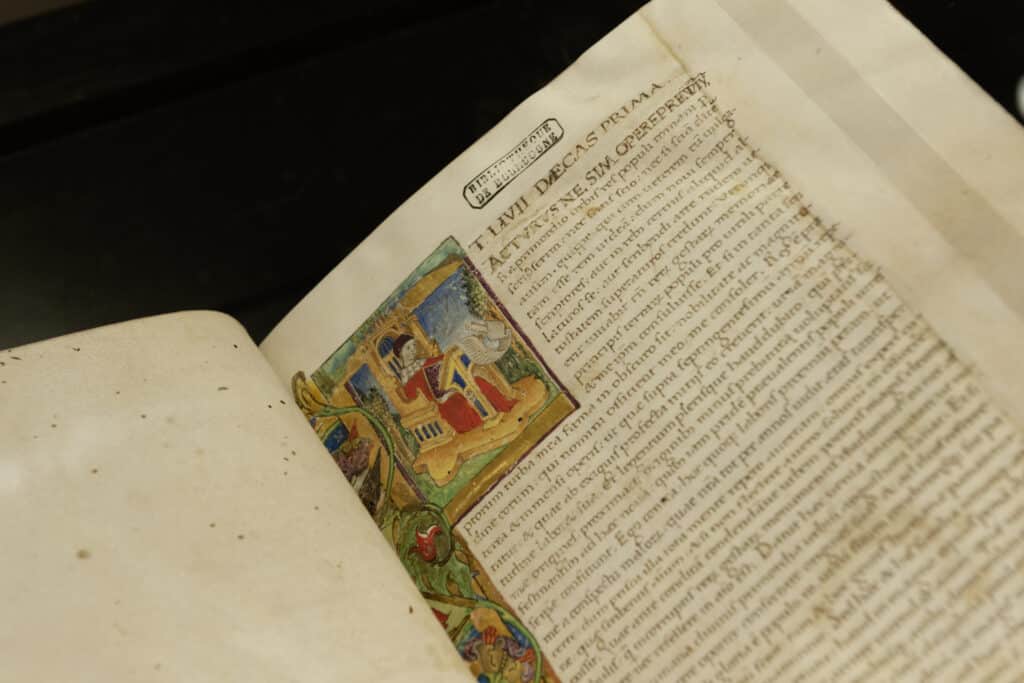

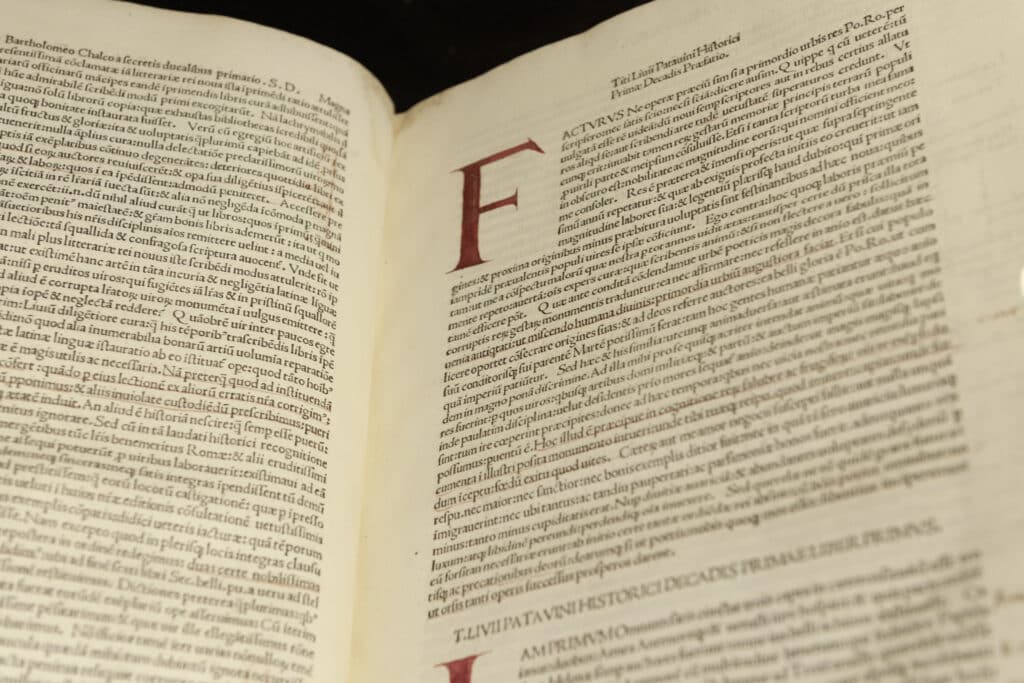

Simple Latin vs. decorated French

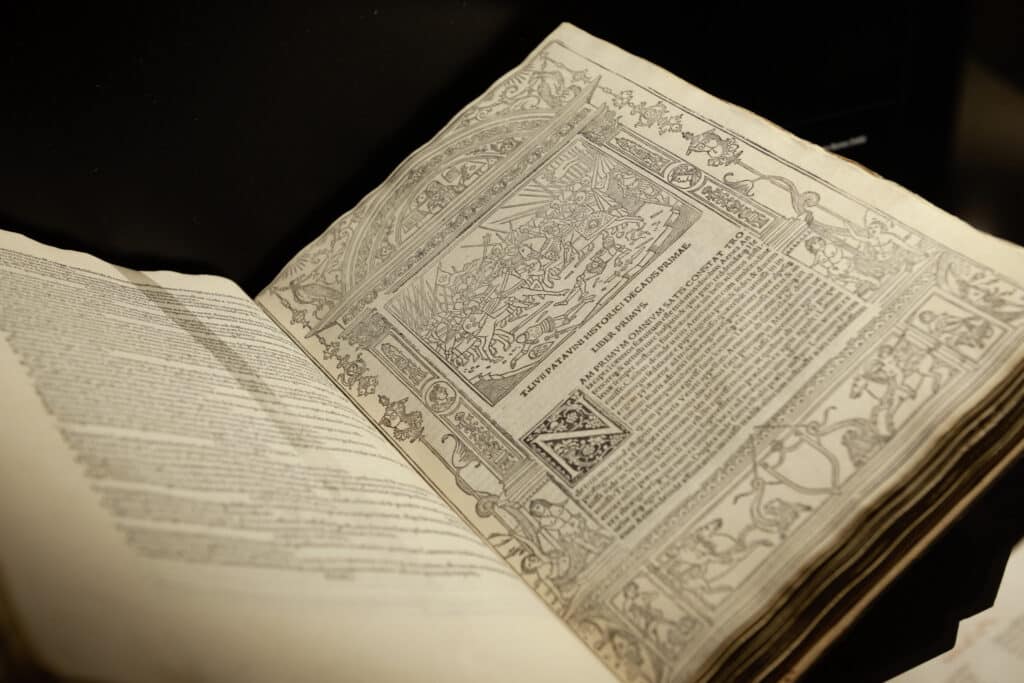

This means there are a great many manuscripts with text by Livy. When laid next to one another, something is immediately noticeable. In general, books with Livy’s text in the original Latin are plainly rendered. Deluxe decorations seem unnecessary: the readability and accessibility of the text are paramount. Indeed, the Latin manuscript is intended for scholars and erudite humanists.

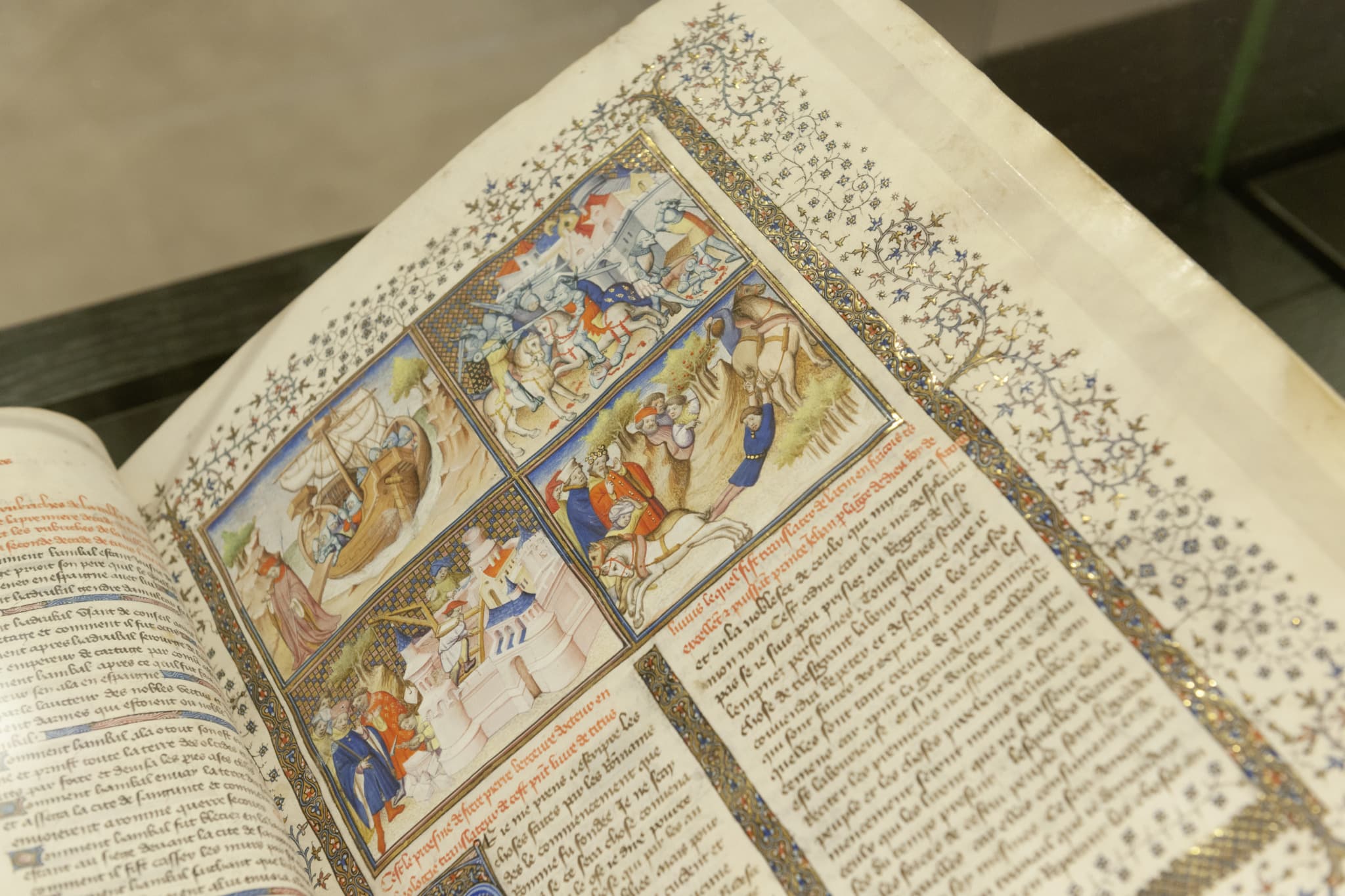

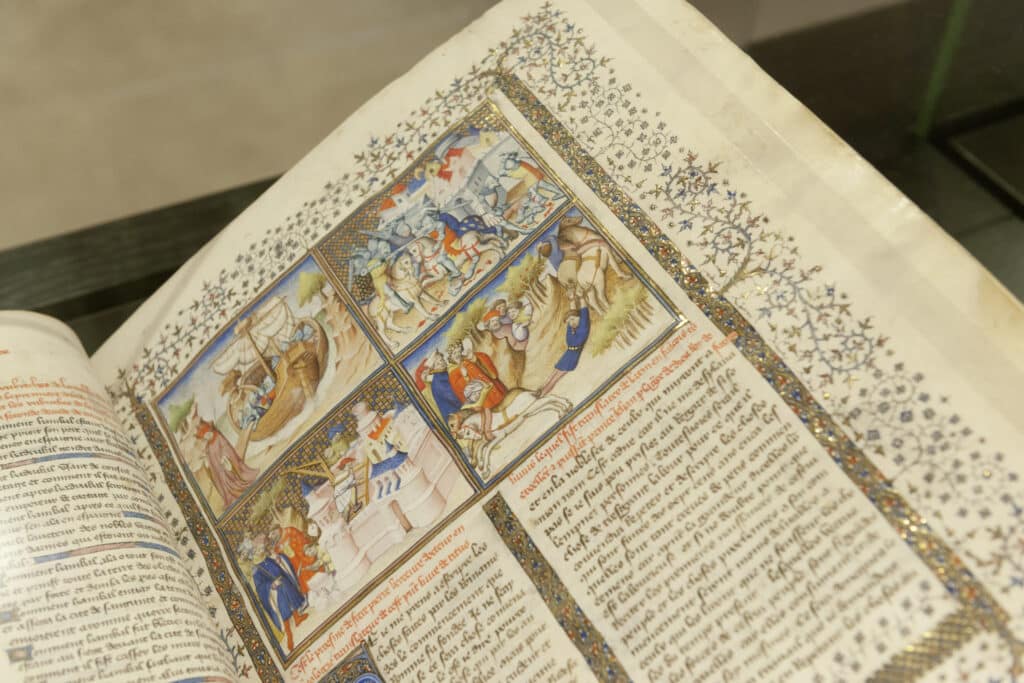

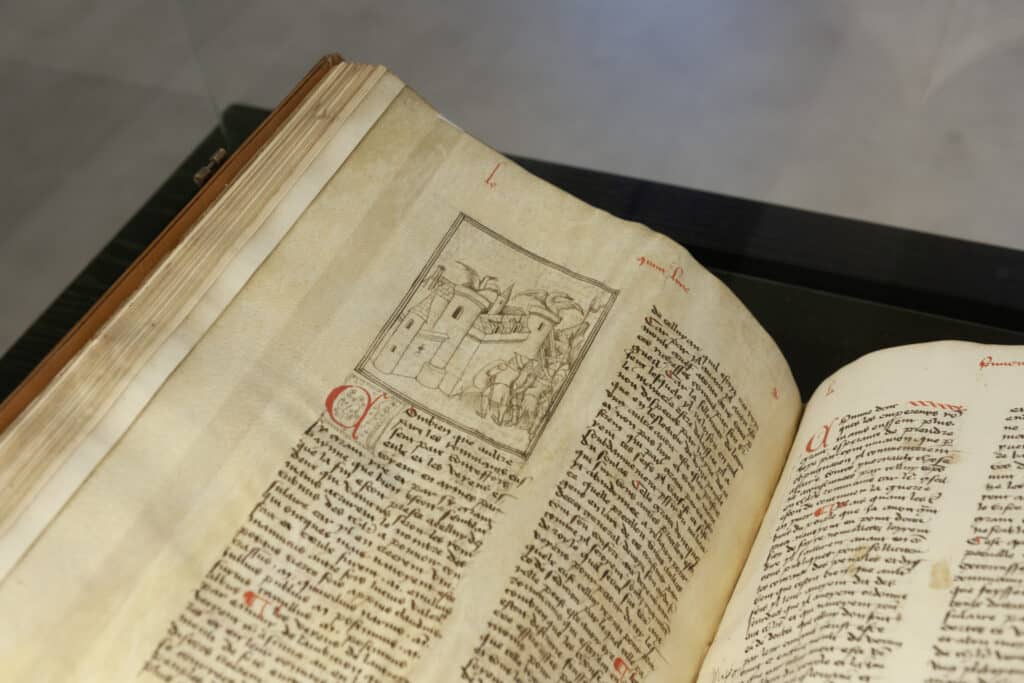

The translations address a different audience, specifically the high nobility and bourgeoisie. They do not know Latin, or do not know enough of it, and have different expectations of a book. A manuscript must exude luxury and reflect their social position. This is why manuscripts with translations of classical authors often have fine initials and sometimes even miniatures.

A mediaeval football match?

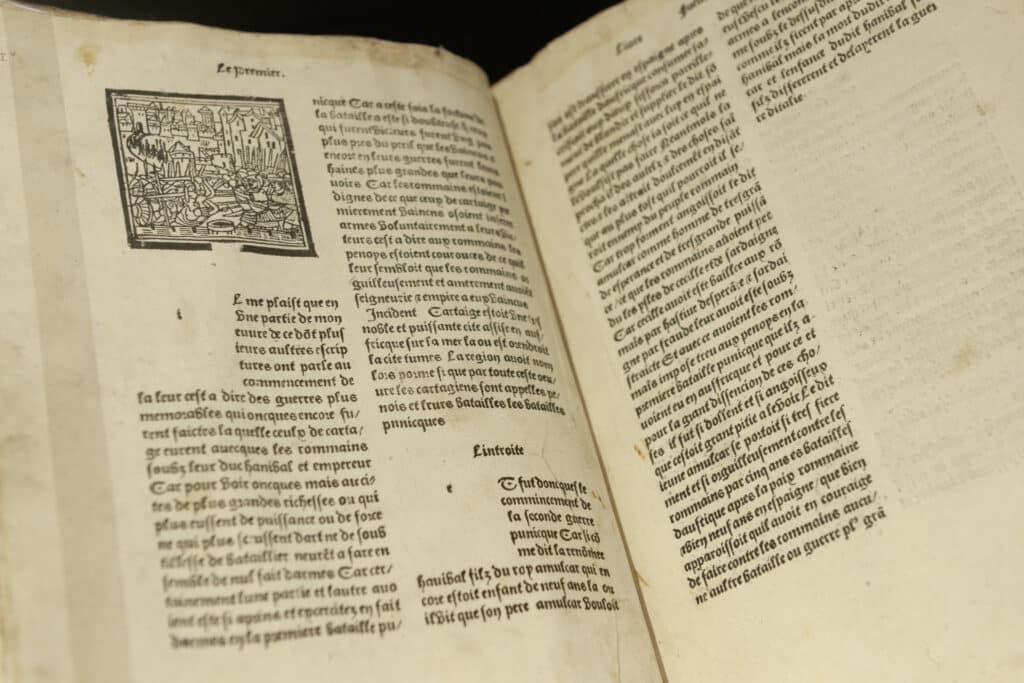

The miniatures depict classical antiquity in mediaeval forms. The Roman soldiers are represented as though they were contemporary mediaeval knights. In the war between Rome and Carthage, the first party can be recognised by the red colour above the suit of armour, the second by the blue one – so just like in a contemporary football match.

Indeed, the classical text would not so much be seen as the history of antiquity by these readers, but more as a kind of heroic tale.

Livy in Latin or in French: they are in fact two worlds, for a different audience, with a different vision of the world and the text.

– Dr. Michiel Verweij, Researcher at KBR

From manuscript to printing

Although much of Livy was read since the Renaissance, in the Middle Ages, he was practically unknown. This (partly) explains why such a large part of his work has been lost. It is nonetheless interesting to look at several versions of his works. We can clearly see the differences between the languages.

We will examine several books from our collection here:

The French translation by Pierre Bersuire

Livy’s gripping account of Rome’s earliest history and the war against Hannibal was translated into French in the 14th century for the French King, John the Good (circa 1350 – 1364). The manuscripts display all the hallmarks of the Burgundian deluxe volumes: written in the “Burgundian bastarda”, in two columns, on deluxe parchment, with fine initials and decorations in the margin.