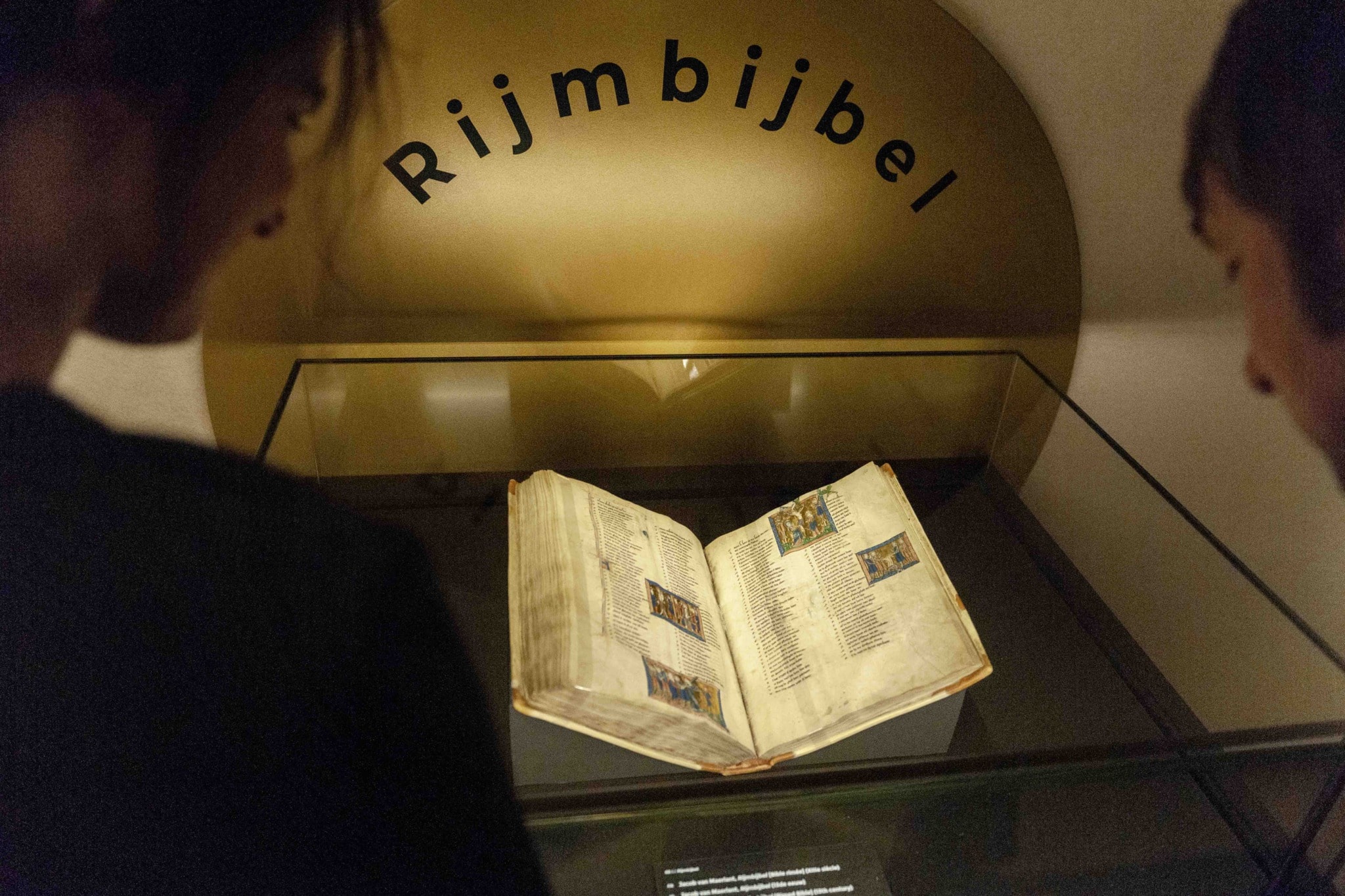

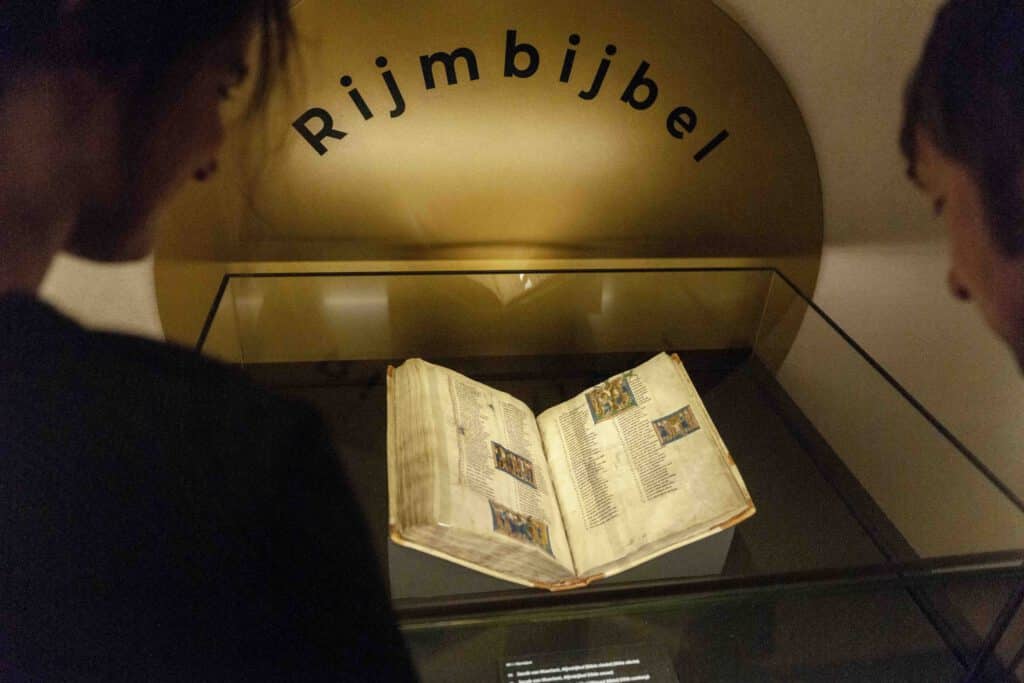

Jacob van Maerlant wrote the very first adaptation of the Bible in the Dutch vernacular, the “Rijmbijbel”, 750 years ago. As the name suggests (Rhymed Bible), the text is written in verse. The copy kept by KBR is particularly special: its provenance shows it to be the oldest illustrated manuscript in Dutch that has been fully preserved. But there are other reasons why it is regarded internationally as a true masterpiece.

Jacob van Maerlant, world-famous in the Low Countries

The 13th-century poet Jacob van Maerlant is one of the best-known and most prolific Middle Dutch authors. His goal was to make the knowledge which was only available in Latin, also available in the common language or vernacular.

Although he wrote a number of chivalric stories early in his career, he later concentrated on what we would now call “non-fiction”. He is thus perhaps best known as the author of the “Spiegel historiael”, a world chronicle, or “Der naturen bloeme”, a nature encyclopaedia. And contrary to what we might expect today, he wrote all his texts in rhyme.

For the “Rijmbijbel”, the very first adaptation of the Bible stories in Dutch, he relied on various sources, some of which were already well known in ecclesiastical and intellectual circles, but which then also became available to those who had not mastered Latin. When it came to actual biblical history, he added a Middle Dutch adaptation of a text about the decades after Christ’s death on the cross, the “The Wrath of Jerusalem”.

His texts were widely distributed in the Low Countries among the nobility, the bourgeoisie and the clergy. This wide range is extraordinary and applies to very few other Middle Dutch texts. The writer exerted huge influence on later authors, from whom he is distinguished by his versatility and particular zeal.

Cultivated public

Maerlant’s “Rijmbijbel” was a popular work that was copied for two centuries. It is not known how many copies were ever produced, but today there are 64 texts that bear witness to the “Rijmbijbel”. This is a very high number for a text dating from the 13th century.

Maerlant’s texts circulated in higher circles, including the Dutch count’s court. He wrote the “Rijmbijbel” in his own words, commissioned by a “lieve vrient” (dear friend), although we do not know to whom this refers. In any case, the “Rijmbijbel” appealed to a cultured and middle-class audience: some of the surviving manuscripts are particularly precious.

More than 150 miniatures

One of these luxury manuscripts was produced in Maerlant’s own time and presumably during his lifetime. The book in KBR’s possession (ms. 15001) dates from the last quarter of the 13th century and is among the oldest illustrated manuscripts in Dutch.

In the limited company of more or less contemporaneous examples, the Brussels manuscript stands out because of its size, the high number of miniatures and the fact that the book has survived almost completely.

With its 159 miniatures and 4 margin decorations, the manuscript is the richest illustrated surviving “Rijmbijbel”. Only in this copy was the “Wrath of Jerusalem” text also decorated with illustrations; in other manuscripts, this section has an opening miniature, at most.

Colourful stories

The miniatures in this “Rijmbijbel” were not just put in for illustrative purposes. They are often placed at a story transition, bringing structure to a text that does not otherwise consist of separate chapters. Moreover, the thumbnails probably made it easier to remember the content of the text.

A pictorial tradition for Biblical stories existed in the late thirteenth century. The miniatures depicting the Old Testament in this “Rijmbijbel” are inspired by contemporary Bible illuminations and illustrations from psalters. Yet the miniatures also attest to the creativity of the miniaturist who sometimes converted Maerlant’s text directly into images or added to it himself.

Endangered miniatures

More than a quarter of a century ago, it was found that flakes of gold leaf in the “Rijmbijbel” were coming off. However, the planned restoration was postponed because the techniques then in use proved inadequate. Consultation of the manuscript was then banned, to prevent further damage.

Thanks to the support of the Abbé Manoël de la Serna Fund of the King Baudouin Foundation, KBR was able to start conservation treatment in 2014, using adapted technology. As a result, you can now finally admire the manuscript again.

High-tech diligent work

To allow for a meticulous preliminary study, the manuscript was (very carefully) digitised. This provided images that map, in great detail, even the damage to the miniatures, which is barely visible to the naked eye.

After a thorough analysis, consolidation was then implemented. This is a process that aims to restore lost compactness and adhesion between individual layers, preventing material loss. Thanks to this restoration, the manuscript is once again accessible.

Students at work

In parallel with the restoration of the manuscript, students at the universities of Antwerp, Utrecht and Leiden set to work on the contents of the book. In Utrecht, art history students studied the miniatures and placed them in the story of the “Rijmbijbel” and the “Wrath” under the guidance of Martine Meuwese.

In Antwerp, Frank Willaert and Patricia Stoop guided students of Middle Dutch through translating the accompanying text from the “Rijmbijbel” into modern Dutch.

Several years later, Bram Caers set students at Leiden University to work studying the remaining passages from the “Wrath”. The results of those working groups formed the basis of the public book “De Rijmbijbel van Jacob van Maerlant: Het oudste geïllustreerde handschrift in het Nederlands”.